- In the second generation of the One Child Policy in China, four grandparents and the two ‘only child’ parents await the delivery of a baby, creating a demand for a perfect outcome (Hellerstein et al., 2015).

- Asian community attitudes and beliefs towards babies with impairments, and the impact on parents and families, are explored in the Disability section of this resource.

Asian perceptions about health and illness

Caring for Asian Children Resource

eCALD Supplementary Resources

Expectations of a perfect baby

Babies head

- Some Asians, especially Hmong people, believe that touching a baby’s head draws out the soul or spirit. If the spirit leaves the child, the child will get sick. It is also believed that making a fuss over a child will draw attention to the baby and the child’s spirit might be stolen as a result of this. (Livo et al., 1991).

- Hmong are ethnic groups from the mountainous regions of China, Vietnam, Laos, Myanmar and Thailand. (Wikipedia,2017).

![]()

Suggested approach:

- Precautions should be taken, unless it is required for medical reasons. For example, newborn hearing testing equipment is placed around the head of the newborn. An explanation about the procedure and risk must be provided to parents (and grandparents) to avoid refusal or non-consent for the testing.

Birth and postnatal care

Each family may have different rites and taboos regarding birth, and postnatal care.

Birth

- For many Asian women coming to maternity wards may be their first experience in a New Zealand hospital. They may not know what to expect and may be confused and frightened by the unfamiliar care and environment. Most Asian women would like to have a female relative, usually their mother or mother-in-law, with them during their birth.

![]()

Suggested approach:

- Explain the services and ask about the woman’s expectations and needs during birth.

Postpartum practices

- Traditional postpartum practices are influenced by the belief that they help women rejuvenate, rehabilitate, recover and regain their energy. The practices are believed to prevent the ailments of old age such as: poor vision, digestive disorders, uterine prolapse, back pain, aching joints, headaches, varicose veins, wrinkling of the skin and premature aging. It is generally believed that postnatal women require a lot of rest and should be relieved of household chores for a month (30 days) or more after the birth. Women are not expected to exercise. During this period, new mothers are not allowed to shower or shampoo. Traditional Chinese women must observe stringent dietary restrictions eg they are expected to eat “yang” foods, which are neutral and warm and are beneficial for restoring the body to its natural balance of “yin” and “yang”. All foods must be cooked and served hot including water. Some of the special soups or foods may have a strong smell that may not be appealing to westerners.

![]()

Suggested approach:

- Find out before the birth what the family requires, identify any specific-cultural requirements, acknowledge and respect families’ practices and offer culturally appropriate support eg offer the woman other options such as warm or hot water to sponge herself with if she is not showering.

Newborn Hearing Testing

- Newborn hearing testers need to be aware that some cultural practices or beliefs may impact on the uptake of newborn hearing screening.

- Asian women observing traditional postpartum practices may spend most of their time resting after the birth of their baby.

- Some Asian women are not happy with any intervention that involves their babies’ head and are unfamiliar with the newborn hearing testing programme and the benefits.

- Some grandparent(s) who are with the new mother may refuse newborn screening even though the mother agrees to the procedure.

![]()

Suggested approaches:

- It is important for Newborn Hearing Testers (NHT) to complete the newborn hearing test before the woman is discharged. NB Asian women who are observing traditional postpartum practices strictly may be expected by their mother or mother-in-law not to leave the house during the postnatal rest period. Asian women may refuse to come into the hospital for newborn hearing testing after they have been discharged.

- Ask the midwife to remind the mother about the screening. Preparing the mother for the NHT visit to the birthing suite to do the newborn screening will make it more acceptable to carry out the procedure while the woman is resting in her room.

- Explain the screening process, the risks and benefits of the screening to the new mother (and the grandparent(s) who may be involved in the care of the newborn).

- Providing screening information in the client’s language is helpful or engaging an interpreter when explaining the screening process to non-English speaking women or grandparents.

Hearing Loss and Hearing aids

- Some Asian families are reluctant or may refuse to let their child, who has been diagnosed with a hearing loss, wear the prescribed hearing aids because it makes the child’s disability visible.

![]()

Suggested approaches:

- If a parent refuses to let their child wear the prescribed hearing aids, health practitioners need to explore the reason why and explain the impact of the hearing loss on the child’s development. Explain that it is mandatory that their child wear the hearing aids and that not allowing a child to wear hearing aids may be considered child neglect. The consequences may lead to a referral to the Ministry for Vulnerable Children (MVCOT, formerly Child Youth and Family services). NB Asian parents may not be familiar with the NZ definition of child neglect or the seriousness of a referral to MVCOT. All efforts must be made to encourage the family to cooperate and to explain the consequences to ensure compliance.

Infant care

- Traditionally, Asian women are considered weak and ‘toxic’ during this period, as evidenced by the presence of postpartum discharge. Postnatal discharge or lochia is thought to be contagious and for that reason other women are discouraged from coming into contact with it. It is a belief that the follicles expand during birth, leaving the new mother weak and vulnerable to “cold”, “air”, “wind” or “rain”, and thus she is discouraged from going out of the house. In some cases new mothers are not expected by their mother or mother-in-law to leave the house during the postnatal rest period. The mother will not therefore visit their newborn who is in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. This may be misunderstood by nursing staff as poor maternal bonding with the newborn.

- Some Asians believe that praise should never be given to a newborn as this invites the attention of demons and ghosts who may steal the child because of his/her desirability. Their preference is that the baby be referred to with unfavourable words such as “you are ugly”. This is common among Hmong an ethnic group from China, Myanmar, Thailand, Vietnam) (Franklin, 2005).

- Some Muslim and Hindu families also keep a lamp burning throughout the night for seven days to drive evil spirits away from their newborn babies. (Franklin, 2005).

- The ‘Mongolian blue spot’ (a bluish pigmentation) is common at birth amongst Indo-Chinese and other Asian babies, and persists until the age of 18 months or two years.

- Some babies may be over-wrapped and sleep in a prone position.

- Some babies may be separated from their mother for at least the first 24 hours, to allow the postpartum mother to rest.

- For some, grandmothers, particularly the father’s mother, are often very involved with the new baby and the new mother’s recovery. Their authoritative position should be acknowledged when caring for the mother and the baby, during teaching sessions.

- Babies in some Asian cultures may not be named for 1-3 months. For example, in Chinese culture, the baby may initially be given a nickname to be used until a formal name is given. A child's formal name is usually picked by its grandparents traditionally. A baby’s naming ceremony is very important because Chinese people believe that one's name can influence everything that happens in life. How this ritual is celebrated depends more on each specific family than on traditional rules.

- Some may not like to have a baby crying too much or some may not like to leave the baby lying on a bed too much. So Asian mothers/ grandparents may carry their infant quite often rather than leave their baby crying as this is considered neglect or bad parenting. It is common for the parents to have the baby “rooming-in” in their bedroom and this practice may persist until the child is more than one year old.

- Many Asian women who are urbanised and live in big cities in Asia are not familiar with benefits of breastfeeding. There is much anxiety and stress about breastfeeding. Some mothers believe that formula provides more nutritional content than breast milk and will supplement breastfeeding. Additionally, for some families, the grandparents are the primary care giver.

![]()

Suggested approaches:

- Explain to the woman the benefits of breastfeeding and bonding while the newborn is in the neonatal intensive care unit. Explore the potential reasons for the woman refusing to visit the newborn (avoid assuming the mother has bonding or child neglect issue).

- Explain to the woman what is expected from them for the care of their newborn, when the newborn is under intensive care. NB they may not be familiar with service expectations.

- Explain to the mother (and grandparents) that breast milk is sufficient for all their baby's nutritional needs.

Male Circumcision

- Circumcision is performed on all male Muslim children. The timing of this varies but it must be done before puberty (Queensland Health and Islamic Council of Queensland, 2010).

- Additionally, circumcision is common in the Philippines and South Korea; for 13% in Thailand (Castellsague et al., 2005; Gopal, 2009]; and between 17 to 20% in some regions in China (Ben et al., 2008; Sullivan et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2009).

- NB Female Circumcision is illegal in New Zealand. For further information see the Maternal Health for CALD women: Resource for Health Providers working with Asian, Middle Eastern and African Women (Waitemata DHB, eCALD® Services, 2016g pp 40-41).

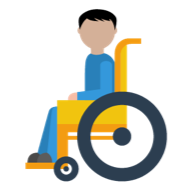

Child Disability

- Disability carries stigma in most cultures. Attitudes towards treatment, care, opportunities and inclusion for children with disabilities and their families can vary considerably in Asian communities compared to New Zealand policy on disabled rights and entitlements (Hasnain et al., 2008; Ministry of Social Development, 2016; Pinto & Sahur, 2001).

- The different explanations Asian cultures have for the causes of disability (eg shame, karma, curse and punishment) and community attitudes impact on how families care for children with disabilities. This can range from disavowal, hiding, segregation and acceptance through to elevation – treating people with impairment as special (Waitemata DHB, eCALD® services, 2016d).

- Beliefs about keeping children with impairments outside public view, coupled with cultural/religious explanations about the causes of disability can affect the extent of care and support accessed and accepted by a family (Galloway et al., 2003; Kim-Rupnow, 2001; Liu, 2001; Wang, Michaels & Day, 2011).

- The stigma associated with disability, a lack of disability services in countries of origin and settlement issues can leave Asian families isolated, stressed and difficult to engage with (Galloway et al., 2003; Kim-Rupnow, 2001; Liu, 2001; Wang, Michaels & Day, 2011).

- To improve families’ knowledge, understanding and acceptance of services, involve a cultural case worker (when available) to liaise with and support the family (Harris, 2004, Goode, 2003; Mortensen, Latimer & Yusuf, 2014).

- To ensure engagement, include a Cultural Case Worker and / or an interpreter in consultations from the outset, and identify and include the key decision maker and caregiver/s for the child in every session.

- Where possible, provide information in the family’s language, give clear explanations of roles and services, and take time to explain why different services and professionals are involved.

- Remember that not all people belonging to the same culture will subscribe to the culture’s ascribed beliefs; some may hold traditional explanations yet follow mainstream medical interventions, whilst others may have rejected cultural explanations altogether.

The Islamic perspective on disability

(Waitemata DHB, Child Women & Family Services, 2013)

- There are a number of aspects of Islam that are helpful for families coping with disability. Muslims believe that everything that happens in life, whether good or bad, is from Allah. This is understood as fate (qadr) and acceptance of fate is an important part of a Muslim’s daily life

- Having a family member with a disability can be seen as a test of faith, an elevation or higher rank in piety or an opportunity to acquire sustenance (rizq) by caring well for a person with a disability.

Cultural perspectives on disability in Muslim communities in New Zealand

(Waitemata DHB, Child Women & Family Services, 2013)

- Cultural views often differ significantly from the Islamic perspective of disability. Stigma and shame in the community are big issues that families face.

- The causes of disability may be viewed in many different ways, for example: the result of the sinful actions of the parents or of ancestors; a curse from God; a source of shame; a blessing; or a test of faith.

- According to some cultural views in home countries, disabled people are sometimes perceived as having the power to “infect” others with the same affliction and are therefore avoided.

- Cultural views of disability vary among different cultural groups within the Muslim community. In many home countries, the word ‘disability’ means physical disability. An intellectual disability or mental health issue is not seen as a disability. A child with an intellectual disability might be labelled ‘crazy’ or considered possessed by a ‘jinn’ (spirit). This difference in terminology can cause confusion for parents.

- Disabilities acquired through accident or war may be seen as more acceptable than congenital impairments. In some cultures, people with disabilities are hidden from the community.

- In New Zealand, the understanding and attitude of many Muslim community leaders towards disability, particularly those working in the health or social services sectors, has changed, as have the attitudes of those who have lived in New Zealand for some time. However, other members of the community, and particularly older family members tend to hold traditional cultural views about disability and they are also often the decision makers.

Further information on Muslim perspectives on disability are available from: Waitemata DHB, Child, Women & Family Services (2013).Working with Muslim Families and Disability. Auckland: WDHB Child, Women & Family Services. Retrieved from: http://www.ecald.com/assets/Resources/Toolkit-Muslim-Families-Disability.pdf.

![]()

Suggested approaches:

- Become aware of the different explanations regarding disability (eg karma, punishment, witchcraft or curse).

- Use an interpreter and / or a Cultural Case Worker to assist engagement with the family, especially for the first meeting and assure confidentiality.

- Explain your role to the family.

- Identify the decision maker.

- Identify the main caregiver.

- Work with the family and understand their goals.

- Explain that there may be other practitioners involved in the child’s care (and what their roles are).

- Explain how the New Zealand health system works for their family.

- Provide translated information on how to use New Zealand health and disability services (see Resources section).

Working with Muslim families with a child with a disability

- Building trust is most important in order to engage the family and should be the main focus of early encounters. The family is a very important part of a Muslim’s life, so it is important to include the extended family.

- Decision-making: Find out who the decision maker is and include this person in discussions early on if possible. Sometimes the decision maker lives offshore. Also find out who is the main carer, and include the decision maker and the main carer in the development of care plans.

- Avoid making generalisations and stereotyping people. It’s best to ask if you don’t know.

- Remember that the family’s goals for their child with a disability may be different from the goals of health and disability services. You may be able to understand the family’s expectations better by asking how the situation would be managed in their home country. A good approach is to learn what the family’s goals are and support these while negotiating to have the service’s goals agreed to as well. Health services may not have been available in their home country or they may have been organised differently, so how services work may need to be explained (sometimes many times).

- Because disability support services may not have been available in home countries, parents may not understand their purpose. They may need help to understand the roles of agencies eg Needs Assessment and Coordination Service (NASC) and of practitioner role eg Speech Language Therapist (SLT). Remember to explain your role and the role of others involved in treatment, therapy or care. Be prepared to do this more than once.

- Disability support services are sometimes refused because the family expects to care for the family member themselves. It might be helpful to remind the family that it is alright to accept support from others.

- It is good to acknowledge that any religious methods of treatment (as long as they are within New Zealand law) can work well alongside western methods, and that any form of treatment is from Allah.

- Finding a culturally appropriate carer can be difficult. It is not unusual to find that a family has been assessed as eligible for carer support, but cannot find anyone to take up the role. Using individualised funding can be helpful in employing a language matched/ culturally appropriate carer.

- If offering a respite care service, be sure that religious requirements are accommodated. The provision of halal food and provision for prayer are two important considerations.

- Participation and inclusion of disabled children in activities and in the community is an issue for some families. In the Auckland region there are CALD disability support groups available. Further information can be found on the eCALD® services website: www.ecald.com/news-updates/news/cald-child-disability-newsletters and the Disability Connect website: http://disabilityconnect.org.nz/.

Medications

- Some Asian families hold beliefs that any kind of medication taken continuously has side effects (Stewart & Das, 1997).

- However, on the other hand, when parents/grandparents are seeing a GP or a specialist, many will expect something tangible, like a prescription or an injection, as part of western treatment. This is often a standard practice in their countries of origin. Just talking can be seen as a waste of time and money (especially if they are paying for the service).

- Traditional Asian families would consider Western medicine as useful in acute situations, and traditional treatments are useful for address underlying causes and longer term health. Some clients may use western and traditional treatments concurrently and the possible interactive effects of medicines may need to be assessed.

![]()

Suggested approaches:

- If no prescription or intervention is being offered to the patient, explain the cause of the illness and the reason for no intervention or medication prescribed. Offer practical help or health tips where possible to keep the client engaged.

- Assess whether clients are using western and traditional medications/ treatments concurrently. NB questions could include:

- What do you think caused this illness?

- How do people from _____ usually treat this illness?

- What have you done already to cope with / treat this illness?

- What other medications are you taking?

- Who prescribes your other medications?

- What do you do when you run out of medication?

- Can you access similar source/s of help here in New Zealand?

Festive seasons

- There is a belief that taking medicine or brewing medicine on the first day of the Chinese New Year will result in the person getting ill for a whole year. For some traditional Chinese families when family members are sick, they may break their medicine bottles in the belief that this custom will drive the illness away in the coming year.

- Some Asians may not attend scheduled medical appointments during festive seasons for the same reason.

![]()

Suggested approaches:

- To avoid non-attendance by patients who believe in such taboos, confirm with CALD patients that the appointment date suits them and reschedule if it coincides with any festive seasons.

- To confirm appointments with non-English speaking patients, ask for an Appointment Confirmation Service from an interpreting service to assign an interpreter to contact the patient to confirm the appointment date and time over the phone. Also remind the patient to cancel the appointment with the service if they are unable to attend (advise them to ask an English speaking family member or friend to contact the service if they can’t speak English).

Food

- Asians have specific food requirements when sick (due to Body Balance beliefs, and to cultural dietary norms differing from western ones.

- Chinese people prefer hot meals and hot drinks when they are sick eg hot tea, clear soup.

- Rice is standard for every meal for Indian families. Meals are usually served with sambhar, rasam (thin soup) and dry curried vegetables. Indian women after birth prefer traditional food called “katlu” or “panjiri”, which provides a “hot effect” for restoring energy. Many Hindus have a vegetarian diet and will not eat any foods with meat products eg yoghurt which contains gelatine.

- For Koreans, rice is the main staple along with vegetables and small amounts of meat. There is no preference for hot meals and hot drinks when unwell.

- Some Asians may avoid certain foods (eg egg, beef or seafood) after an operation.

- Asians may like to have pasta (with soup), porridge with vegetables and a small helping of pureed meat or fish.

- Rice culture is popular in Asian countries whereas bread culture does not give patients feelings of adequate nutrition or an adequate meal. Hard rice is not enjoyed by Asians when they are unwell. They prefer soft rice cooked in a rice cooker.

- Asians may avoid oil/butter/cheese when sick.

- Asian families/friends may cook food for patients, whenever possible.

- Asians may prefer home-made baby food eg congee rather than the ready-made baby food (cereal/ jar food).

- Asians may feel that being on a drip will not give them enough nutrition and begin to feel weak after a few days if not fed by mouth.

- Islam has rules about the types of food which are permissible (halal) and those which are prohibited (haram). The main prohibited foods are pork and its by-products, alcohol, animal fats, and meat that has not been slaughtered according to Islamic rites. While most prohibited foods are easy to identify, there are some foods which are usually halal that may contain ingredients and additives that can make them unacceptable. For example, foods such as ice cream may contain pork by-products such as gelatine, which is considered unacceptable.

![]()

Suggested approach:

- Consult with families about their food preferences and any special requirements (eg halal, vegetarian, etc) for their children or young person. They are usually happy to advise and/or supplement hospital food when necessary.

Surgery and treatment

Asian people have different perceptions, habits and taboos towards illness, eg some Asian families view surgery as a major big trauma.

- Some Asians may consider chemotherapy toxic and harmful for the child, and may seek alternative treatments.

- After diagnosis is provided, if information about treatment is not provided in a timely manner, some Asian families may take their child back to their homeland for further investigation or treatment.

- Western medications are believed to have side effects and to compromise general health.

- The caregiver for the child in Asian families may take time to consider options, or talk to their husband/father of the child and to older family members.

- Asians may avoid bathing or showering when recuperating from surgery as they are afraid of getting cold.

![]()

Suggested approaches:

- Provide clear explanation of diagnostic tests, surgery or treatment options, process, timeframe and consequences, in the client’s language.

- Assess health literacy and language proficiency and use professional interpreters. (Avoid using the sick child or family members to interpret).

- Seek feedback from families about the information provided to ensure comprehension.

- Offer the option of sponging the child with warm water, if the family refuse bathing/showering after major surgery.

Rehabilitation

Generally Asians have a smaller body build and believe that they need a longer recovery time. They traditionally have a lot of rest when ill and are careful not to over exert themselves when in recovery. Concepts of rehabilitation and exercise may be new to some clients.

![]()

Suggested approaches:

- Ask families about their concept of recovery or rehabilitation.

- If their concept does not include physical activity, explore and negotiate culturally and mutually acceptable activity that could be incorporated into the recovery plan for the child.

- Explain the benefits of the rehabilitation process for the child’s recovery and development and seek feedback from the family about what activity would be considered acceptable and monitor the child’s progress.

Protective Charms

Vietnamese, Cambodian, Thai and Laotian cultures may have protective charms for children in the form of string bracelets or necklaces.

![]()

Suggested approaches:

- Explain to the parents the need to remove the charms for the procedure or treatment. Usually the parents will be happy to do so. They may need to pray before the charms are removed.

- During emergency situations, if the charms are in the way and the parents of the child are not available to ask for permission, it is culturally appropriate to remove and put the charms aside, then return and explain to the parents the medical reasons for the removal, when they arrive.

Paediatric Palliative Care

- The challenge of providing compassionate end-of-life care is compounded when cultural differences occur and there are language barriers.

- Ethnicity and religion influences the acceptability of withdrawal of intensive care treatment (Warrick, Perera, Murdoch & Nicholl, 2011). For example, Muslims believe the deliberate taking of life is unacceptable and some believe that the ‘premature termination of life through acts of omission’ is also against their teachings (Gatrad, 2008). Spiritual leaders may offer support to parents and advice to clinicians with decision-making.

- In Asian cultures, it is the duty of parents to do everything possible to prolong the life of their baby/child.

- Family members’ views may be in conflict with medical views regarding what constitutes the optimum quality of life and end-of-life treatment or care.

- Children in New Zealand with a life-limiting illness die in hospital with a significant influence resulting from ethnic background, diagnosis and referral to the paediatric palliative care (PPC) service. A PPC service was established at the Starship Children’s Hospital in Auckland. This small multidisciplinary team provides care across the hospital to home continuum in greater Auckland, and advice to other healthcare services nationally (Chang et al., 2013).

- Asian children are more likely to die in hospital compared with New Zealand European children. (Chang et al., 2013)

- Asian families are often unfamiliar with advance care plans. They may be reluctant to discuss end of life care for their child, based on the belief that acknowledgement of their child’s impending death may be self-fulfilling.

- Families often choose not to openly discuss death and dying with their child for fear that this will damage his or her hope, causing a poorer prognosis. This can cause conflict between the healthcare team and the family, particularly when the child is an adolescent or young person.

![]()

Suggested approaches:

- Insights into the cultural beliefs which influence family’s preferences about where a child dies will enhance the end-of-life care planning for Asian families (Chang et al., 2013).

- At the end of a child's life, the focus needs to be on quality as defined by the family, not the provider. Supporting parents so that they can fulfil their traditional role as care-givers, protectors, decision makers, providers of love and physical tenderness, and instillers of faith requires an individualised approach to end-of-life care. Respecting beliefs, customs, and traditions with a focus on preserving the integrity and sanctity of the parent–child relationship is of utmost importance in paediatric palliative care (Wiener et al., 2013).

- When working with Asian families who may not have advance care plans or may not be familiar with advance care planning:

- Offer families the opportunity to discuss end of life care and advance care planning with a professional interpreter. A list of Interpreting Service Providers can be found on this site http://www.ecald.com/resources/migrant-and-refugee-services/ or check your DHB/service’s policy on how to access interpreting services. Advance care plans provide shared goals of treatment between family and healthcare professionals that can guide treatment during a period of deterioration and end of life care.

- Avoid using words such as ‘death’ and ‘fatal illness’. (Tse et al, 2003)

- An alternative which may be less threatening is presenting issues to parents in hypothetical terms to determine levels of comfort with planning for end of life care for their child (Wiener et al., 2013).

- Consider referring to, or obtaining advice from the paediatric palliative care team.

- If family choose not to discuss end of life care, contingency plans need to be made in case the child arrives at emergency department in crisis to avoid confusion.

- Contact the child’s general practitioner, primary paediatrician, paediatric team members and emergency department staff with a clinical update and plan.

- The child should be assessed and stabilised in the first instance (Paediatric and Child Health Division of the RACP, 2008).

- Discuss the child’s condition and prognosis with the family.

- Negotiate goals of treatment and discuss management options with the family.

- If there is a conflict with medical views eg the family want to fulfil their duty as parents by prolonging the life of the child:

- Listen respectfully and hear the values and views of family members.

- Demonstrate awareness and understanding of the family’s need to do their very best for their child. It is important to offer advice with empathy and compassion and to help reduce the family’s feelings of anguish about potentially not fulfilling their obligation to do the best for the child from their perspective.

- Explain your concerns about initiating treatment aimed at prolonging life eg causing suffering to the child with little or no benefit, prolonging the dying process, the possibility that ventilation may not be able to be weaned.

- Negotiate a management plan with the family that includes symptom management, psychosocial emotional and spiritual support. This may include a short trial of treatments aimed at prolonging life e.g. antibiotics, non-invasive ventilation. If necessary seek palliative care, ethical and medico-legal advice.

- When spiritual/religious support is needed:

- Identify any spiritual/religious support the family are already accessing and whether they would like referral to additional services.

- If so, ensure that the spiritual/religious leader to be contacted is compatible with the family’s faith (eg Sunni versus Shia, Catholic versus Pentacostal).

- With the consent of the parents and caregivers, access appropriate spiritual /religious support through the spiritual organisations listed on relevant websites.

- If the child is cared for in the hospital, where possible the religious contact should be arranged through the DHB chaplaincy service.

Expressions of grief: loss of a child

- Expressions of grief usually include:

- Personal feelings sadness, anger, guilt, anxiety, and helplessness.

- Physical sensations shock, hollowness in the stomach, tightness of the chest, weakness of the muscles.

- Cognition confusion, disbelief.

- Behaviours sleep disturbances, crying, social withdrawal.

- However Asians may express their grief differently. This will be influenced by many factors including cultural and religious backgrounds.

- In addition to crying, grieving people may shout, bite their hands and fingers, tear out or cut their hair, jump, rock backward and forwards, or sit in a corner with their eyes closed. In some cultures, grieving people may attempt to vomit. Self-harm is an extreme psychological reaction (eg people may cut their veins or attempt suicide), and is a pathological reaction to grief.

- In some cultures, people mourn for their deceased children less than they mourn for deceased adult relatives. In most societies, women are expected to mourn longer and deeper than men. Men are expected to be strong and not to show their emotions (Queensland Health Multicultural Services, 2009).

![]()

Suggested approaches:

- If the couple is distressed, source and refer them to language appropriate psychological support or grief counselling service (if available).

- Try to elicit potential reasons if the couple refuse psychological support.

- If needed and where available, refer him/her or them for a psychiatric assessment.

- Encourage early contact with the general practitioner or other health professional.

- Where available, if the couple is in a state of denial, reassure them that mental health support is available to them.

- Respect their decision not to seek mental health support, as many people prefer coping with grief in a personal manner.

- If available, provide printed information (eg booklet, pamphlet) about grief, preferably in the woman’s or couple’s own language.