The Asian population in the Auckland Region was over 402,000 in 2016 representing 23% of Auckland’s total population (Statistics New Zealand, 2015). The most predominant Asian ethnicities in the region are Chinese (38.5%); Indian (34.6%), Korean (7.2%) and Filipino (7.0%) peoples. Close to a quarter of Asian peoples in the Auckland region have lived in New Zealand for less than 5 years (Walker, 2014).

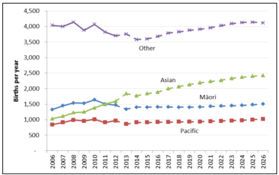

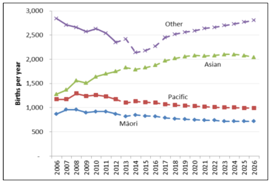

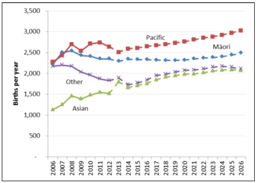

Asian, populations have a much younger age structure than European populations, with relatively high proportions at the child and childbearing ages, and low proportions at the older ages (Statistics New Zealand (SNZ), 2015). In the last decade, there has been a significant increase in births to Asian women in the Auckland region. The following graphs show the Auckland region’s birth numbers and projections to 2025 by ethnicity (Auckland & Waitemata DHB, 2012).

|

WDHB – Asian births are expected to rise from 21% (2012) to 32% (2025). |

ADHB – Asian births are expected to rise from 29% (2012) to 32% (2025). |

CMDHB – Asian births are expected to rise from 18% (2012) to 22% (2025). |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Annually the New Zealand government accepts a UNHCR mandated refugee quota of 750 places. In 2018, this number will increase to 1000 quota refugees per annum. Refugees also arrive as asylum seekers and through the refugee family sponsored category. A quarter of refugee populations are under the age of 15 years (McLeod & Reeve, 2005). Refugees to New Zealand from Asian backgrounds come from: Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Afghanistan, Sri Lanka, Burma, Bhutan and China. Pediatric refugees have complex medical and psychological needs (Rungan et al., 2013). Refugee children are at risk of developmental and mental health problems due to their refugee experiences of trauma, violence and deprivation and of migration stressors on arrival in New Zealand (Rungan et al., 2013).

To begin with, having knowledge of the current demography, health determinants, health utilization and key health issues of Asian children will enhance service planning and development. The next sections will address: the socioeconomic status of Asian populations; the health status of Asian children; child health in refugee populations; and caring for Asian children.